In the last post, I discussed the scriptural evidence for holy images in the Old Testament, specifically in the Tabernacle and Temple. I even showed various places where veneration was given to holy images. I explained how idolatry had a precise definition, often involving creating a body for worshipping the spirit. Of course, none of that happens with icons in an Orthodox Church. This is one way of knowing how an icon of Christ or a saint is not idolatry.

In this post, I would like to discuss how icons express the theology of the incarnation. Many confessing Christians in the Protestant tradition (myself included not long ago) claim that icons are idolatry because they cannot depict the uncircumscribable God. However, this argument is highly damaging to ALL of Christendom and the fundamental Christian belief that the co-eternal Word of God became flesh and dwelt among us (John 1:14). This is because it has the presupposition at the heart of it that claims that the material cannot contain the divine. And thus, if true, Christ would not be able to incarnate.

For me, this was a massive argument to contend with. I remember realizing this while reading St. Theodore the Studite. I was left shocked. Out of one side of my mouth, I confessed as an Evangelical that Jesus Christ is the incarnate Word of God and the second person of the Holy Trinity. Out of the other side, I used the arguments of strict unitarians like Muslims and Rabbinic Jews who deny that their god can enter creation in such a manner. Sure, I confessed and believed in Christ. Still, it is improper to use the arguments and fundamental underlying logic of those who are polemical against the incarnation of Christ to argue against icons. Doing so would mean I undercut the entirety of the thing I confess in Christ and His work.

What Happened in the Incarnation?

Jesus Christ is the Son of God, eternally begotten before all time. John 1:1-4 shows that Christ, the Word, is a person of the Holy Trinity and is not a created being since all was made through Him. He is eternally begotten of the Father outside of time. St. John goes on to say in verse 14, “And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we beheld His glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father, full of grace and truth” (Orthodox Study Bible/NKJV). In the last post, I pointed out Luke 10:21 and 22 as well as Colossians 1:15, where it is explicit that Jesus Christ is the icon (eikōn/εἰκὼν) of the Father. This is also confirmed by John 14:9:

"Jesus said to him, “Have I been with you so long, and yet you have not known Me, Philip? He who has seen Me has seen the Father; so how can you say, ‘Show us the Father?” (John 14:9, Orthodox Study Bible)

St. John of Damascus says:

The Word of God himself is reckoned the hypostasis with regard to the flesh, for God the Word was not united to flesh that already existed in itself, but came to dwell in the womb of the holy Virgin without being circumscribed in his own hypostasis, and gave substance to flesh from the chase blood of the Virgin, flesh that was ensouled with a rational and intelligent soul, and, assuming what is representative of the human substance, the Word himself became the hypostasis with regard to the flesh. As a result, he was a the same time flesh, at the same time flesh of God the Word, at the same time rational and intelligent ensouled flesh, at the same time rational and intelligent ensouled flesh of God the Word. Therefore we do not speak of a human being who has been defied but of God who has been inhominated.1

Jesus Christ, the co-eternal Word of God, of one essence with the Father who eternally begot Him, became flesh so that we may be united with God. This was our “telos” or purpose we had lost in the fall that only the God-Man, Jesus Christ, could restore. Saint Maximus the Confessor says, “For it was fitting for the Creator of the universe, who by the economy of his incarnation became what by nature he was not, preserve without change both what he himself was by nature and what he became in his incarnation.”2

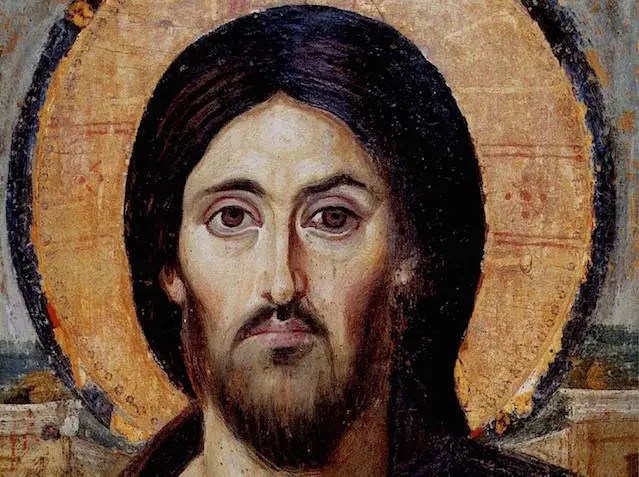

In short, the incarnation of Jesus Christ, its “Cosmic Mystery,” as St. Maximus puts it, is that the eternal word of God put on flesh and entered into creation. This changes everything. This is why the old is made new. This is how we engage in the life of salvation and theosis. I stated in the last post how Deuteronomy 4:15 and 16 shows the reason why God had told Moses they could make no image of Him. They had no form to see. The Father is unknowable in His essence to us. He transcends being and is spirit. We know God through what He reveals to us. But Christ is the Word and Son of God. God entered creation and “dwelt among us” (John 1:14, Orthodox Study Bible). We saw Him. We have a form. This is where St. Theodore the Studite’s arguments come in.

Icons Express the Incarnation

The idea of God entering into His creation and dwelling among mankind, along with His death and resurrection, is central to Christian teaching and theology. These concepts are linked. They are a package deal. For example, you cannot deny the incarnation while accepting the death and resurrection. It just does not logically follow that Christ could experience a physical death and resurrection if He never took on a physical body. Christ says that he is the image of the Father. Worshiping and honoring Christ is worshiping and honoring the Father as what belongs to Christ is God’s and what is God’s is Christ’s since they exist within each other and share one essence (John 16:15). Thus, despite having a material and physical body, one can know and worship the Father through the Incarnate Word of God.

This is where the devastating blow to the Protestant iconoclasm comes in. Any argument against icons can be made against the incarnation of Christ.

You cannot logically affirm the incarnation of Christ and yet be against holy images and icons.

Catharine P. Roth, in the introduction to St. Theodore’s work, says:

"If Christ cannot be portrayed, then either He lacks a genuine human nature (which is docetism) or His human nature is submerged in His divinity (which is monophysitism). The council of Chalcedon (451) had held that Christ was 'in two natures without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.' If Christ’s human is not changed or confused with his divine nature, then He must be able to be portrayed like any human being.”3

You have to contend that Christ was not human but appeared as such (the heresy of docetism) or that the human nature of Christ was absorbed into the divine nature (the heresy of monophysitism). Both are condemned heresies. Most Protestants in the West affirm the Chalcedonian Christology, which states that Christ is “one hundred percent God and one hundred percent man” (as is often put in modern verbiage). Most iconoclast Protestants do not realize their views logically lead to docetism or monophysitism heresies, thus undermining their Chalcedonian Christological confessions.

"For this reason Christ is depicted in images, and the invisible is seen. He who in His own divinity is uncircumscribable accepts the circumscription natural to His body."4

The mystery of the incarnation is expressed. A form has been given for a hypostasis of the eternal Godhead. That image came and took on our humanity so that we could once again become one with God through theosis. He incarnated so that we could become “gods by grace,” as St. Athanasius says.

"Now, because Christ is the eternal God-Man through the hypostatic union of the two natures in the person of Christ, human nature is irrevocably unified with the divine nature because Christ is eternally God-Man.As the God-Man, He ascended to heaven.As the God-Man, He sits on the right hand of the Father.As the God-Man, He will judge the world at the Second Coming.Consequently, human nature is now enthroned in the bosom of the Holy Trinity. No longer can anything cut human nature off from God. Now, after the incarnation of the Lord—no matter how much we separate ourselves from God—if, through repentance, we wish to unite again with God, we can succeed. We can unite with Him and so become gods by Grace."5

The idea of theosis, of being partakers of the divine (2 Peter 1:4), is possible only through the concept of Christ, the Eternal Word, entering into creation and taking on our flesh and being glorified in it. Thus, through emulating Christ and partaking in the sacraments, we can draw closer to God by being co-heirs with Christ (Romans 8:17, Romans 8:29). If we fall into the Christological heresies mentioned above, we deny the possibility of our salvation. And to deny the incarnation is to deny that matter can be deified. To deny icons and their veneration means one cannot honor Christ, who has a physical body like ours, and have such honor pass on to the Holy Trinity’s other persons or to the Father, as Christ Himself claims, because of a frankly Gnostic anti-material view.

Therefore, icons are not idolatry. If we can honor the God-Man Jesus Christ and have such honor pass to the Father (John 5:23), then veneration and honor given to the image of the person of Christ passes on to Christ Himself and therefore on to the Father and the Holy Spirit who share the same essence as the hypostasis depicted in Christ. For example, a soldier who has a picture of his wife and child in a fox hole who kisses the image is not venerating and honoring paper. We all understand he is honoring and loving his wife and child. The same is true for icons. The Christian, when he or she kisses an icon, is kissing and honoring a member of the eternal family in Christ.

Icons and Prototypes

I would point to my previous post on icons and how idolatry had a specific definition regarding making a body for the spirit to inhabit. This means that one has to worship the spirit or creature that is the prototype for the image being made. St. Theodore says:

What do the holy icons have in common with the idols of pagan gods? If we were worshipping idols, we would have to worship and venerate the causes before the effects, namely Astarte and Chamos the abomination of the Sidonians, as it is written, and Apollo, Zeus, Kronos, and all the other diverse gods of the pagans, who because they were led astray by the devil transferred their worship unwittingly from God the maker to the products of His workmanship, and, as it is said, “worshipped the creation instead of the Creator,” slipping into a single abyss of polytheism.6

We worship an actual prototype in the Holy Trinity, and depicting the One who incarnated as us means that hypostasis of the Trinity can be depicted since any human can be depicted. The Holy Spirit and the Father are never shown in icons (except for the symbolic representation of the dove for the Spirit in a few). Thus, no false image or prototype is ever venerated in the holy icons in this regard.

Icons of the Saints

The iconoclast might say, “but what about the depiction and veneration of icons depicting saints? These are not Christ, and it is thus idolatry!”

If Christ is the firstborn of brethren who are partakers of the divine nature (Romans 8:17, 8:29, 2 Peter 1:4), then saints depicted in icons are people who have been perfected in Christ. They are one with God and in communion with Him in a way we cannot comprehend in our material existence. If they are partaking of the nature of Christ and the Trinity, to venerate them is to venerate God and the work of God along with His plan for us. These images are not worshipped as God, however. No drink or sacrifice is offered to the icon of a saint. It depicts a member of the Godly family the Christian reveres and believes is alive in Christ and can intercede for him or her before the Throne of God. But the saints are a topic to cover in a future post.

- of Damascus, J., & Russell, N. (2022). On the orthodox faith: A new translation of an exact exposition of the orthodox faith. St Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

- the Confessor, M., Blowers, P. M., & Wilken, R. L. (2003). On the cosmic mystery of jesus christ: Selected writings from St. Maximus the confessor. St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

- Theodore the Studite, & Roth, C. P. (2005). On the holy icons. St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

- Ibid.

- Kapsanēs, G. (2023). Theosis: The true purpose of human life. Holy Monastery of St. Gregorios.

- Theodore the Studite, & Roth, C. P. (2005). On the holy icons. St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Leave a comment